Sleep is one of the most vital physiological processes human beings undertake, playing a crucial role in physical and mental health, cognitive function, and immune regulation[i]. The quality and quantity of sleep significantly impact overall well-being, yet many individuals struggle with sleep disturbances, often without understanding the underlying cause. Those with mental health conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive disorders frequently experience Emotional Memory Images (EMIs) related to past trauma[ii]. However, a far larger proportion of the global population has suffered adversity—a lesser stress disorder than PTSD but still highly prevalent[iii]—leading to similarly profound disruptions in sleep[iv].

Common sleep disorders associated with EMIs include insomnia and sleep apnoea[v]. Symptoms often range from difficulty falling or staying asleep to irregular breathing patterns that disrupt sleep cycles. A key factor in these disturbances is pre-sleep hyperarousal, where the brain remains hyper-alert to subconscious threats, making relaxation difficult and preventing sustained deep sleep[vi]. This heightened state of alertness can lead to frequent awakenings throughout the night, preventing the body from achieving restorative sleep[vii].

This article proposes that EMIs of adverse life events are a major contributor to pre-sleep hyperarousal, perpetuating sleep disturbances that compromise both mental and physical health. Left unresolved, these disturbances not only affect cognitive and emotional well-being but also have serious physiological consequences, particularly in driving inflammation and chronic pain[viii]. The therapeutic application of the Split-Second Unlearning (SSU) model may provide an effective approach to clearing EMIs, improving psychophysiological health through better sleep quality[ix]. The implication of this approach extends to sleep specialists, mental health practitioners, osteopaths, and individuals seeking non-clinical solutions to chronic sleep and pain disorders.

Case Vignette: The Client who was More Flexible After Guided Meditation.

Client Z mentioned that they awoke each morning stiff and in pain, it would take until lunchtime before he felt he could move around comfortably. He then remarked “On Wednesday’s I’m pain free and flexible all afternoon, thanks to my guided meditation class”. How could one hour of guided meditation give him three hours relief from osteoarthritis? Why doesn’t he awaken flexible after eight hours sleep? Could it be that he was in a freeze stress response while sleeping, flooding his body with cortisol and inflammation? These are the thoughts that ran through the authors mind, and I invite you to hold them in yours as you read on.

What is the Split-Second Unlearning Model?

The Split-Second Unlearning model (SSU) proposes that first-time traumatic, adverse or emotionally overwhelming experiences, real or imagined create EMIs. These EMIs remain within the mind’s eye, activating a freeze response whenever a similar context or situation occurs. SSU is the process by which a practitioner can identify the subtle non-verbal cues, indicating EMI access, and interrupt this connection. SSU suggests long-term EMI triggering leads to chronic pain and disease as the continuous firing of the stress response takes its toll on the body.

Definition and Attributes of Emotional Memory Images

“Trauma induced, non-conscious, contiguously formed, multimodal mental imagery, which triggers an amnesic, anachronistic, stress response within a split-second.”[x]

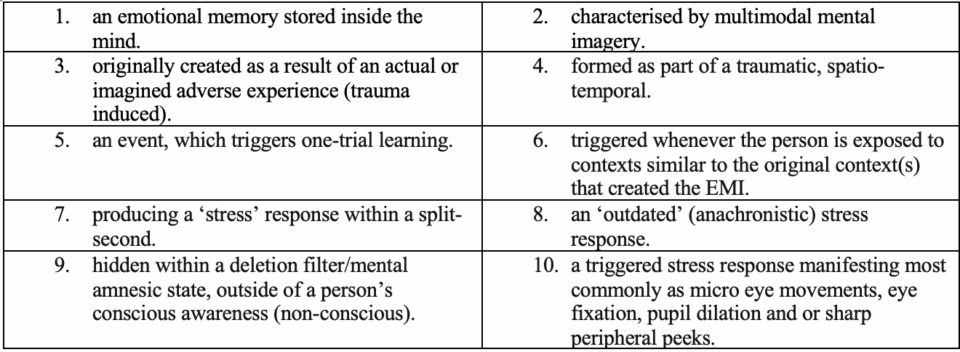

The definition identifies an EMI as:

Please Note

Point 9 above identifies why a client can never point to an EMI as their presenting issue. The practitioner must therefore proceed to support the client to bring the EMI into their conscious awareness.

How Emotional Memory Images Influence Sleep

When we experience stress while awake, the body often responds with a sharp intake of breath, a hallmark of the fight/flight/freeze survival mechanism[xi]. This reaction prepares us to confront danger, flee from it, or remain perfectly still in hopes of evading detection[xii].

During sleep, however, it has been proposed that the same survival response manifests differently v. When an EMI resurfaces, the mind conjures a metaphysical predator—an imagined threat that the brain believes is approaching. In response, the freeze mechanism activates, momentarily halting breathing to immobilise the sleeper. This brief apnoea may have evolved as a defence mechanism, keeping the body still to avoid detection while simultaneously arousing the sleeper to prepare for escape.

While this survival strategy may have served our ancestors well, in the modern context, it creates a cascade of problems. Unresolved, these split-second pauses in breathing can extend into longer apnoea/hypoxia events[xiii], disrupting the restorative processes of sleep and perpetuating conditions such as insomnia, chronic fatigue, other sleep-related health disorders as well as pathological pain.

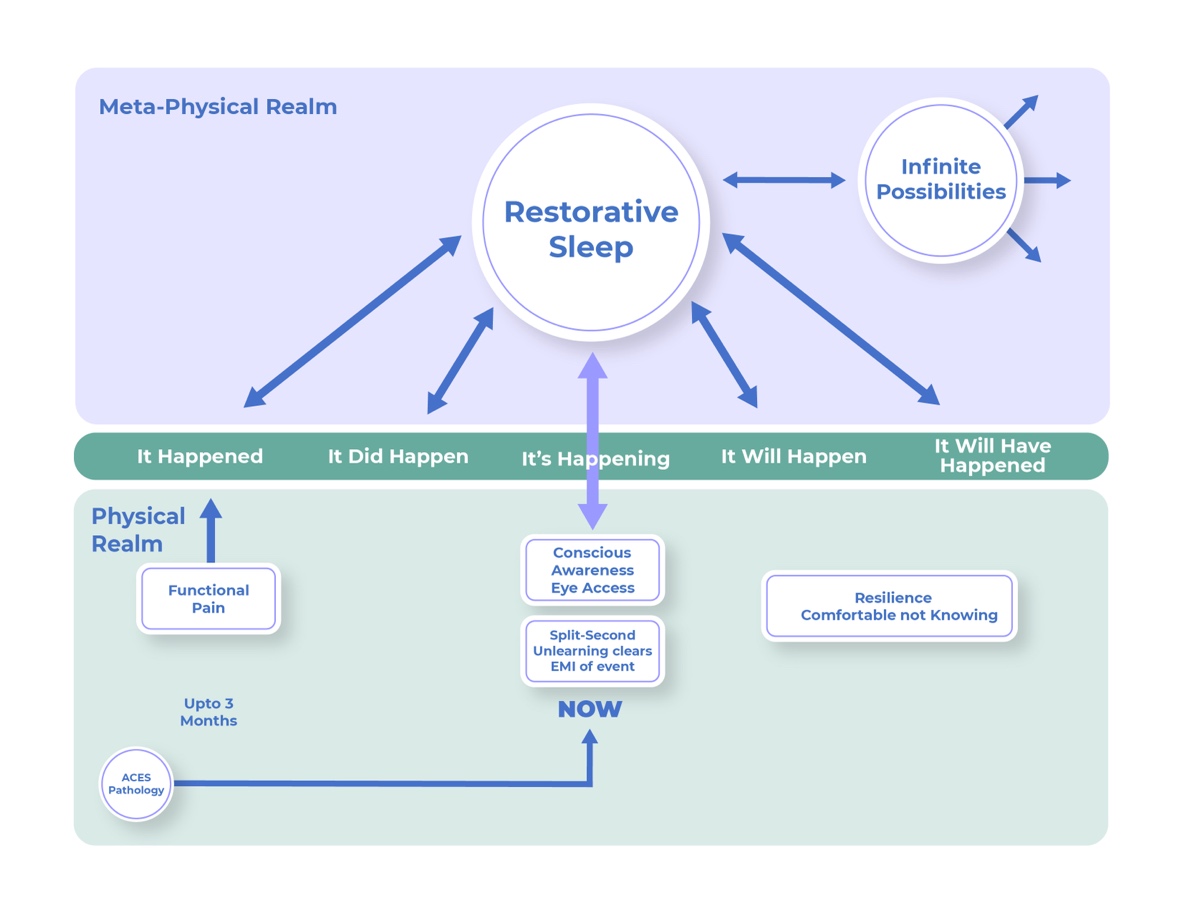

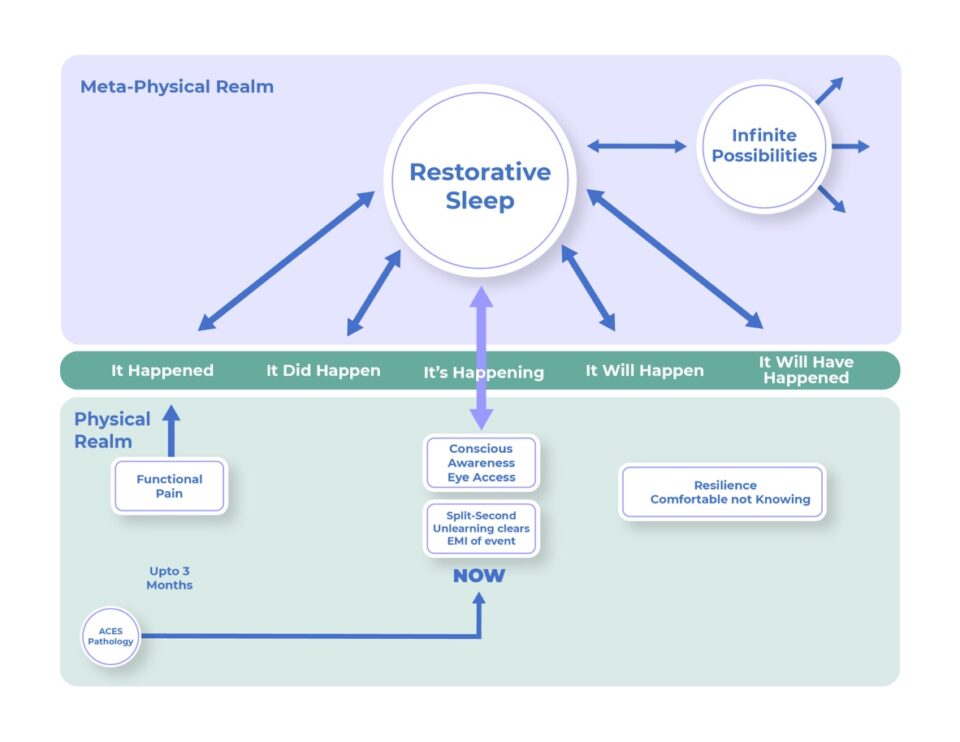

The Role of Split-Second Unlearning in Pathological Pain

Pathological pain can be closely linked to EMIs and the SSU framework through the way past experiences influence the perception and persistence of pain. If an EMI is associated with a past injury or distressing event, the brain may continue to reproduce the pain response even after the physical cause has healed. This can lead to pain without ongoing tissue damage, reinforcing the cycle of pathological pain (see image 1). Clearing EMIs can transform pathological pain. SSU removes these outdated patterns, allowing the body to return to an adaptive stress response (see image 2).

From Sharp Intakes of Breath to Apnoea in Sleep

The transition from waking stress responses to sleep-related apnoea reveals the brain’s adaptive survival mechanism. During waking moments, a sharp intake of breath signifies the body’s readiness to act. During sleep, however, the same physiological fear response shifts into momentary breath-holding, an unconscious attempt to maintain stillness and evade the predator in the mind’s eye. The standard Apnoea/Hypoxia Index (AHI) measures the number of apnoea events lasting over ten seconds per hour. These longer events are clinically significant, but what about the countless shorter ones that go unnoticed? SSU shifts the focus to these micro-events, revealing how even fleeting disruptions— which may be caused by EMIs— grow from molehills into mountains within the meta-physical realm.

While the freeze response immobilises the body, it also perpetuates arousal. This elevates cortisol and systemic inflammation, reinforcing the PAIN (Past Adversity Influencing Now) framework (image 1 & 2)[xiv]. PAIN contends prior negative experiences can keep individuals trapped in a specific time perception, affecting their pain experience; time and pain are complexly connected[xv] This keeps the nervous system in a heightened state of vigilance, increases pain sensitivity, and impairs emotional regulation, decision-making, and recovery—critical for high-performance individuals like athletes and executives—while perpetuating a cycle of poor sleep and distress.

Testing the Sleep Pain Hypothesis

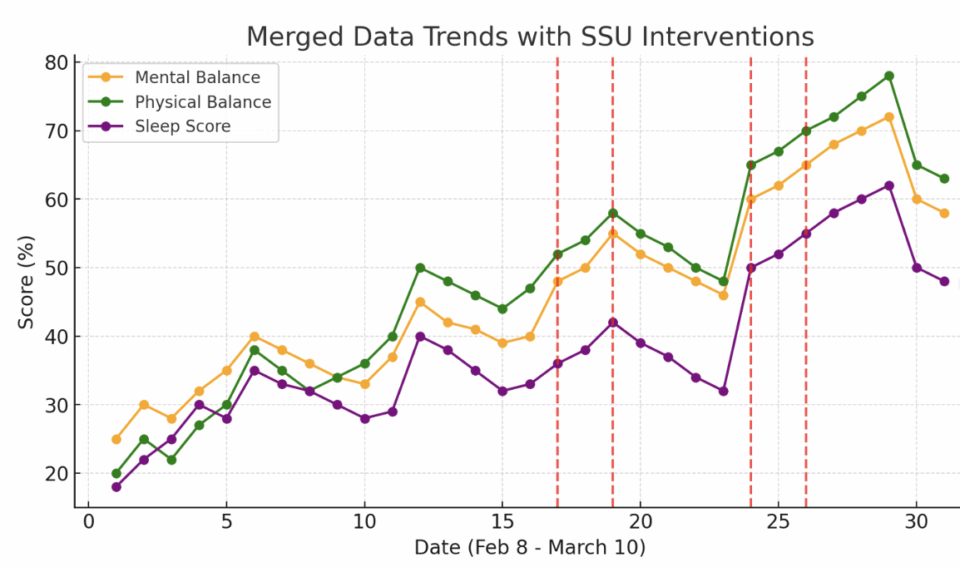

Five client’s in private practice were invited to test the following hypothesis – Can clearing EMIs enhance physiological recovery, reduce pain perception and promote overall health. Participants wore a Fitbit device for a month and data was captured via BioRICS gold standard sleep algorithm[xvi]. Three clients completed the process with the following observations:

1. Sleep Improvement Reduces Inflammation

- Better sleep is linked to lower cortisol levels, reducing chronic inflammation. Deep sleep triggers growth hormone release, essential for tissue repair and pain relief. Post SSU sleep scores increased especially after 1st March. A positive indication

2. Clearing EMIs Lowers Stress & Pain Perception

- EMIs drive autonomic nervous system dysregulation, keeping the body in fight-or-flight mode. Clearing EMIs via SSU unburdens the nervous system, lowering pain sensitivity and preventing stress-induced inflammation.

3. Physical Recovery & Pain Reduction

- Higher physical balance scores post-SSU suggest reduced systemic stress and better recovery. Inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) are suppressed when stress and sleep debt decrease, leading to less joint/muscle pain.

Data Showing Improvements using MindReset Coaching

Conclusion:

- The trend of improved sleep following SSU sessions aligns with a decrease in stress-related inflammation and pain. This supports the hypothesis that clearing EMIs enhances physiological recovery, reducing pain perception and promoting overall health. Objective data to corroborate client feedback. More research is needed.

A New Perspective on Pain and Sleep Osteopaths work with the body’s innate ability to self-regulate and heal, yet unresolved EMIs can act as hidden barriers to recovery by perpetuating hyperarousal and disrupting sleep quality. This cycle of psychophysiological dysfunction sustains chronic pain and systemic imbalance. Integrating the SSU model into osteopathic practice offers a holistic approach to breaking this cycle—restoring coherent sleep patterns, enhancing autonomic balance, reducing inflammation, and optimising musculoskeletal recovery. By addressing the subconscious triggers underlying pain and poor sleep, osteopaths can provide deeper, longer-lasting relief and expand their therapeutic reach, offering new hope to those trapped in persistent pain and disrupted sleep.

[i] Jackson, M. L., & Drummond, S. P. A. (Eds.). (2024). Advances in the psychobiology of sleep and circadian rhythms. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003296966

[ii] Varma, M. M., Zeng, S., Singh, L., et al. (2024). A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental methods for modulating intrusive memories following lab-analogue trauma exposure in non-clinical populations. Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 1968–1987. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01956-y

[iii] Hosseini-Kamkar, N., Lowe, C., & Morton, J. B. (2021). The differential calibration of the HPA axis as a function of trauma versus adversity: A systematic review and p-curve meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 127, 54-135.

[iv] Coronado, H., Bonilla, G. S., Shircliff, K., Sims, I., Flood, E., Cooley, J. L., & Cummings, C. (2024). Considering the associations of adverse and positive childhood experiences with health behaviors and outcomes among emerging adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 244, 105932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2024.105932

[v] Hudson, M., & Chaudhary, N. I. (2023). A perspective on adversity, emotional memory images and pre-sleep arousal in sleep disorders. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14878.92485

[vi] Pesonen, A. K., Makkonen, T., Elovainio, M., Halonen, R., Räikkönen, K., & Kuula, L. (2021). Presleep physiological stress is associated with a higher cortical arousal in sleep and more consolidated REM sleep. Stress, 24(6), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2020.1869936

[vii] Nicolaides, N. C., Vgontzas, A. N., Kritikou, I., et al. (2020). HPA axis and sleep. In K. R. Feingold, B. Anawalt, M. R. Blackman, et al. (Eds.), Endotext [Internet]. MDText.com, Inc. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279071/

[viii] Li, M. T., Robinson, C. L., Ruan, Q. Z., et al. (2022). The influence of sleep disturbance on chronic pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 26, 795–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-022-01074-2

Haack, M., Simpson, N., Sethna, N., et al. (2020). Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: Potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0439-z

[ix] Hudson, M., & Johnson, M. I. (2021). Split-second unlearning: Developing a theory of psychophysiological dis-ease. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 716535. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716535

[x] Hudson, M., & Johnson, M. I. (2022). Definition and attributes of the emotional memory images underlying psychophysiological dis-ease. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 947952. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.947952

[xi] Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L., & Carrive, P. (2015). Fear and the defense cascade: clinical implications and management. Harvard review of psychiatry, 23(4), 263-287.

[xii] Taschereau-Dumouchel, V., Michel, M., Lau, H., & et al. (2022). Putting the “mental” back in “mental disorders”: A perspective from research on fear and anxiety. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(3), 1322–1330. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01395-5

[xiii] Pépin, J.-L., Bailly, S., & Tamisier, R. (2019). Big data in sleep apnoea: Opportunities and challenges. Respirology, 24(10), 985–994. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13669

[xiv] Hudson, M., & Johnson, M. I. (2023). Past adversity influencing now (PAIN): Perspectives on the impact of temporal language on the persistence of pain. Frontiers in Pain Research, 4, Article 1244390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2023.1244390

[xv] Rey, A. E., Michael, G. A., Dondas, C., Thar, M., Garcia-Larrea, L., & Mazza, S. (2017). Pain dilates time perception. Scientific Reports, 7(1), Article 15682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15982-6

[xvi] BioRICS. (n.d.). Mindstretch for individuals: Improve your mental balance. https://www.biorics.com/mindstretch/mindstretch-for-individuals/