Introduction: The Great Memory Puzzle

For more than a century, neuroscience has been chasing memory like a mirage. We can measure its traces, manipulate its correlates, even describe the molecular changes that accompany learning, but no one has ever pulled a memory out of a neuron and said, “Here it is.”

This puzzle has haunted psychology and biology alike. Where is memory stored? Is it etched in synapses? Is it distributed across circuits? Or might we be asking the wrong question altogether?

From Karl Lashley’s mid-century hunt for the engram, through Francis Crick’s reductionist “astonishing hypothesis,” to Donald Forsdyke’s extracorporeal model and Bruce Lipton’s cellular insights, science has inched toward an unsettling possibility: memory may not be confined to the brain at all.

Layered onto this is a radical new idea: Emotional Memory Images (EMIs) -trauma snapshots projected into peripersonal space. If memory is extracorporeal, EMIs are the visible glitches of trauma: projections from the cloud into awareness, distorting psychophysiology until cleared.

This article traces the evolution of these ideas – from rats and scalpels to quantum fields and hive minds – and asks: could the future of medicine lie not in chemistry but in coherence?

Lashley and the Great Memory Hunt

In the mid-20th century, psychologist Karl Lashley set out to locate the engram – the physical trace of memory. Using rats trained to navigate mazes, Lashley surgically removed sections of their brains to see if specific memories vanished.

What he found was frustrating: cutting out one part did not erase one memory. Instead, the rats seemed to retain their skills, albeit less efficiently if more tissue was removed. Lashley concluded that memory was strangely distributed, not neatly localised. He called this equipotentiality.

Modern neuroscience has confirmed part of this: memory recall correlates with activity in various regions – hippocampus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex. But these are correlates, not storage.

It’s like looking inside a radio and expecting to find Frank Sinatra hiding under the wires. You see circuits, dials, and signals moving, but the song itself isn’t inside.

Lashley’s legacy was unsettling: maybe we’ve been hunting in the wrong place.

Francis Crick and the Astonishing Hypothesis

If Lashley showed us what memory was not, Francis Crick tried to show us what it must be.

Having co-discovered DNA’s structure, Crick turned to neuroscience. His Astonishing Hypothesis (1994) made a stark claim:

“You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behaviour of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”

Crick’s reductionism was galvanising. Neuroscience doubled down on mapping circuits, hunting for the neural correlates of consciousness (NCCs), building connectomes, and modelling synaptic plasticity.

But decades later, the core riddle remains. We can watch networks fire when you recall your grandmother’s face, but no one can say: “Here, in this cluster, is the memory itself.”

Crick’s hypothesis was bold – but like the parable of the 17 camels, it may have been incomplete. The sons in the story cannot divide 17 camels into halves, thirds, and ninths until the wise uncle lends them an 18th camel. Suddenly, the math works.

Crick’s framework kept adding tools inside the closed system – but never considered adding the missing “camel”: the possibility that memory lies outside the brain.

Forsdyke’s Extracorporeal Hypothesis

Enter Donald Forsdyke, Canadian biologist, who confronted cases that should not exist.

In The Lancet (2007), doctors reported a 44-year-old French civil servant with severe hydrocephalus. His brain cavity was 90% filled with fluid; the cortex was reduced to a paper-thin rim. By all accounts, he should have been incapacitated. Yet he was married, employed, and functioning – his IQ a modest but workable 75.

He was not alone. Other such cases exist – people with drastically reduced brain tissue but preserved cognition.

If memory were stored purely in neurons, these individuals would have been blank slates. Yet they lived ordinary lives.

Forsdyke proposed a radical answer: memory may be stored extracorporeally – outside the brain, in a kind of informational cloud field. The brain is not a warehouse but a receiver, processor, and transmitter.

Like a computer accessing cloud storage, the brain doesn’t need to contain the files to use them.

This echoes Bohm and Pribram’s holographic models, Shannon’s information theory, and quantum non-locality. But Forsdyke grounded it in biology: hydrocephalus survivors are living proof that memory is not just in grey matter.

Emotional Memory Images (EMIs): Projections from the Cloud

If memory resides extracorporeally, how does trauma appear?

This is where the EMI hypothesis extends Forsdyke. EMIs are trauma snapshots that fail to integrate. Instead of folding into the fractal web of experience, they are projected from the extracorporeal cloud into peripersonal space – the mind’s-eye field surrounding the body.

Clinically, people experience them as flashbacks, intrusive images, sudden anxiety, or a “frozen” sense of self.

Therapy, then, is not about rewriting neurons. It is about dissolving projections. Split-Second Unlearning™ interrupts the EMI in situ, releasing the frozen file back into coherence.

This reframes trauma not as an internal wound but as an external projection -something that can be directly engaged with, observed, and cleared.

Clinical Implications: From EMIs to Noncommunicable Disease

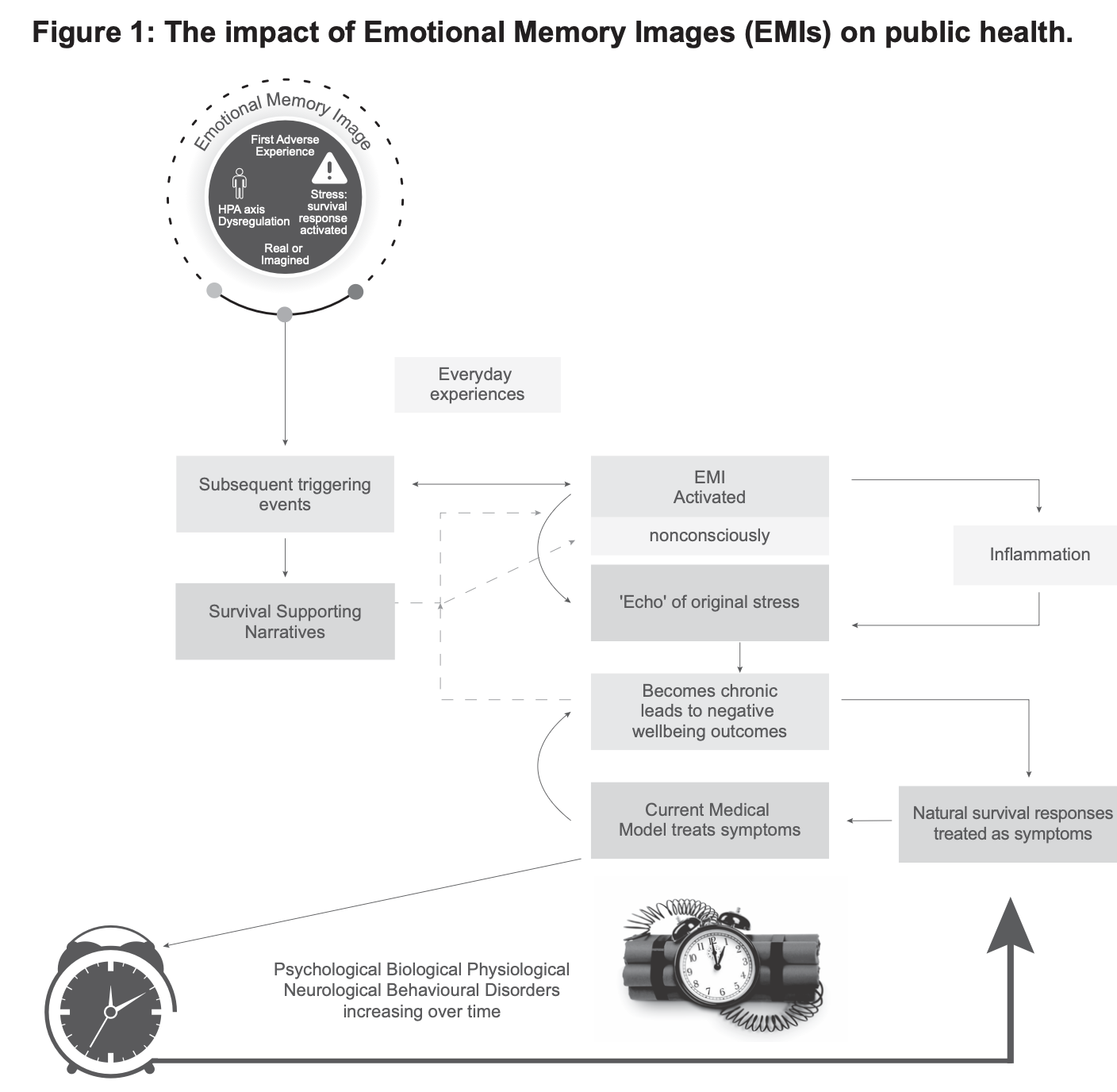

This projection model has profound implications.

Modern medicine treats depression with SSRIs, anxiety with benzodiazepines, inflammation with biologics. These drugs can mute symptoms – but if the true driver is an EMI projection, then they are like turning down a fire alarm while the fire still burns.

Most trauma is undiagnosed. Few people carry a PTSD label, yet many live with unprocessed adversity: neglect, bullying, loss, unsafe environments. These experiences etch EMIs that loop silently in plain sight.

The consequence is chronic stress. The HPA axis stays activated, cortisol floods tissues, and the immune system slips into dysregulation. The result is chronic low-grade inflammation – now recognised as a unifying factor in depression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, obesity, and cancer.

This links trauma directly to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) – the leading global killers.

Public health implications are huge:

- Trauma screening should be as routine as blood pressure checks.

- Clearing EMIs could reduce drug reliance and cut healthcare costs.

- NCD prevention must include trauma control.

Like infection control transformed 19th-century medicine, trauma control could transform the 21st.

Bruce Lipton and the Hive Mind

Biologist Bruce Lipton argued in The Biology of Belief that the intelligence of a cell lies in its membrane, not its nucleus. The membrane senses the environment, receives signals, and directs behaviour. DNA provides the blueprint; the membrane provides the interface.

Scale this up: the human body, with 37 trillion cells, is a vast network of interfaces. Each cell is like a node. Together, they form a hive mind – an integrated organism connected to information fields beyond itself.

Forsdyke’s extracorporeal cloud + Lipton’s cellular membranes = a new vision. The body is a hive, constantly interfacing with a larger informational field.

When trauma strikes, EMIs become glitches in the hive – corrupted files projected back into awareness, distorting coherence across the entire organism.

Therapy restores the hive’s coherence, debugging the signal, allowing trillions of cells to return to harmony.

Fractals, Quantum Fields, and the Nature of Reality

Coherence is not just a metaphor – it is the language of nature.

From the branching of trees to the structure of lungs, from coastlines to neural dendrites, life is patterned in fractals. These repeating forms allow information to be carried efficiently across scales. Richard Taylor’s research shows that viewing fractals lowers stress – as if our physiology recognises its own blueprint.

But trauma breaks fractal coherence. An EMI is a frozen file that refuses to resonate. Instead of flowing with the living pattern, it sits outside it, looping in isolation.

On the quantum scale, reality itself behaves like this. Particles do not sit neatly in place. They pop in and out of observable existence, flickering between potential and manifestation. Consciousness and memory, too, may operate on this rhythm – not stored as objects, but arising as patterns in fields of potential.

Forsdyke’s extracorporeal cloud, Lipton’s membranes, and fractal biology converge here: memory may be less a thing and more a dance of coherence across scales.

EMIs, then, are interruptions in that dance. Therapy is not fixing matter but restoring rhythm – allowing the hive to resonate again with the fractal, oscillating fabric of reality.

9. The Evolution of Ideas: A Timeline

- Karl Lashley (1930s–50s): The engram hunt fails. Memory appears distributed.

- Francis Crick (1990s): Astonishing Hypothesis – reductionism rules, but no engram found.

- Donald Forsdyke (2000s): Memory is extracorporeal, stored in a cloud field.

- Bruce Lipton (2000s): Cells as membrane interfaces, organism as hive mind.

- Matt Hudson & Lisa Hudson (Today): EMIs as projected trauma snapshots, disrupting coherence but clearable in an instant.

Each thinker added a piece. EMIs integrate them into a framework that is both scientific and clinically actionable.

This model revolutionises how we think about disease, and how we organise health systems around it.

- Mental health redefined. Depression may not primarily be a serotonin imbalance, nor anxiety a matter of “chemical wiring.” Instead, both may be the body’s response to unprocessed EMI projections. loops of trauma frozen outside awareness but continuously replayed in peripersonal space. This reframes therapy from managing neurotransmitters to dissolving frozen files.

- Chronic illness as trauma-shadow disease. Heart disease, diabetes, autoimmune conditions, and even some cancers can be seen not merely as the result of lifestyle or genetics, but as the physiological shadow of unresolved trauma. The frozen EMI distorts the hive’s coherence, producing chronic inflammation that manifests as noncommunicable disease (NCDs).

- Economic transformation. Current systems pour billions into drug treatments that mute alarms but do not extinguish the fire. Trauma clearance could drastically reduce reliance on chronic medication, saving health systems billions while increasing wellbeing and productivity. The return on investment is not only financial but generational.

- Policy revolution. Just as infection control – clean water and sanitation transformed 19th- and 20th-century health, trauma control could be the equivalent revolution of the 21st. Screening for ACEs and EMIs could become as routine as measuring blood pressure. Preventative trauma clearance could become the frontline defence against NCDs.

- Salutogenic shift. Traditional medicine focuses on disease – pathology, breakdown, deficit. A salutogenic lens focuses instead on health creation (salutogenesis), asking how coherence can be restored. In this view, what we call “dis-ease” is not merely dysfunction but a signal, a call to resolve hidden trauma and re-establish harmony.

- Body–mind unity. This model erases the artificial divide between mental and physical health. An EMI is simultaneously psychological and physiological: a cognitive glitch and an inflammatory driver. Treatment, therefore, must address the whole person, not fragmented systems.

- The bee-hive analogy. Bees defend their hive from a hornet by swarming together, generating heat, and restoring balance. The hive acts coherently, visibly, to protect itself. The body, too, rallies against intruders – but when the intruder is an EMI, the swarming happens invisibly, within stress systems and immune responses. The danger is that this hidden defence never resolves, leaving the body in endless alarm. Trauma clearance is like helping the bees finally expel the hornet.

- Reinterpreting symptoms. Symptoms can be seen not as the problem but as the body’s attempt at resolution. Panic attacks, flare-ups of autoimmune disease, or mood swings may be the hive “swarming” to signal the presence of a hidden EMI. This changes the therapeutic stance: instead of suppressing symptoms, we listen to them as guides to hidden trauma.

- Generational healing. EMIs often stem from childhood adversity. Left unresolved, they cascade through life and may even influence epigenetic expression, transmitting risk to the next generation. Trauma clearance, then, is not only personal healing but intergenerational prevention – breaking cycles of suffering before they embed in families and societies.

- Cultural coherence. On a wider scale, societies too can carry EMIs: cultural traumas, wars, displacements, systemic oppressions. Public health grounded in EMI theory would not only heal individuals but could also address collective trauma, restoring coherence at the cultural “hive mind” level.

Taken together, these implications point to a new era in health. A 21st-century revolution lies not in more pills but in coherence – restoring the fractal rhythm of the hive, clearing the frozen projections of trauma, reconnecting the self to the informational field in which it truly lives.

11. Conclusion: Beyond the Skull, Toward Coherence

The search for memory has taken us from rats and scalpels to neurons and networks, from reductionism to fields, from cells to hives, from fractals to quantum flickers.

The conclusion is as radical as it is inevitable:

- Memory is not confined to tissue.

- Trauma is not just in the head.

- Healing is not just chemical.

We are fractal beings in a flickering universe, plugged into a hive mind, interfacing with a cloud of extracorporeal memory.

EMIs are the frozen files that trap us in loops. Therapy is the release.

The future of medicine, then, is not about controlling symptoms but about restoring coherence. Just as infection control transformed public health, trauma control could transform our age. The astonishing hypothesis is not that we are “nothing but neurons,” but that we are everything but neurons – patterns of coherence, flickering in and out of reality, always more than the sum of our parts.

Take a look at this short video for an overview