[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.27.4″ global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.16″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.16″ custom_padding=”|||” global_colors_info=”{}” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.27.4″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” hover_enabled=”0″ global_colors_info=”{}” custom_padding=”||8px|||” sticky_enabled=”0″]

Recent developments in memory theory, notably Donald Forsdyke’s hypothesis of extracorporeal “cloud storage” offer a provocative lens to reconsider the storage and retrieval of Emotional Memory Images (EMIs). Forsdyke suggests that memory may extend beyond the brain’s physical architecture, potentially involving non-local repositories akin to cloud computing’s distributed data access. This challenges the conventional view that memory is solely a neurobiological phenomenon.

This idea echoes Immanuel Kant’s distinction between noumena (things-in-themselves) and phenomena (things-as-perceived) (see this video for a short explanation). EMIs—vivid imprints often forged in moments of acute trauma—might be conceptualised as non-local entities stored beyond immediate conscious access, perhaps within a noumenal domain. This reframing suggests that subconscious triggers, which elicit rapid emotional and physiological responses without conscious mediation, may draw from such an extracorporeal source. If correct, this could explain the limitations of traditional therapeutic approaches that target only neural restructuring to resolve deep-seated trauma. ( watch this video for more insight)

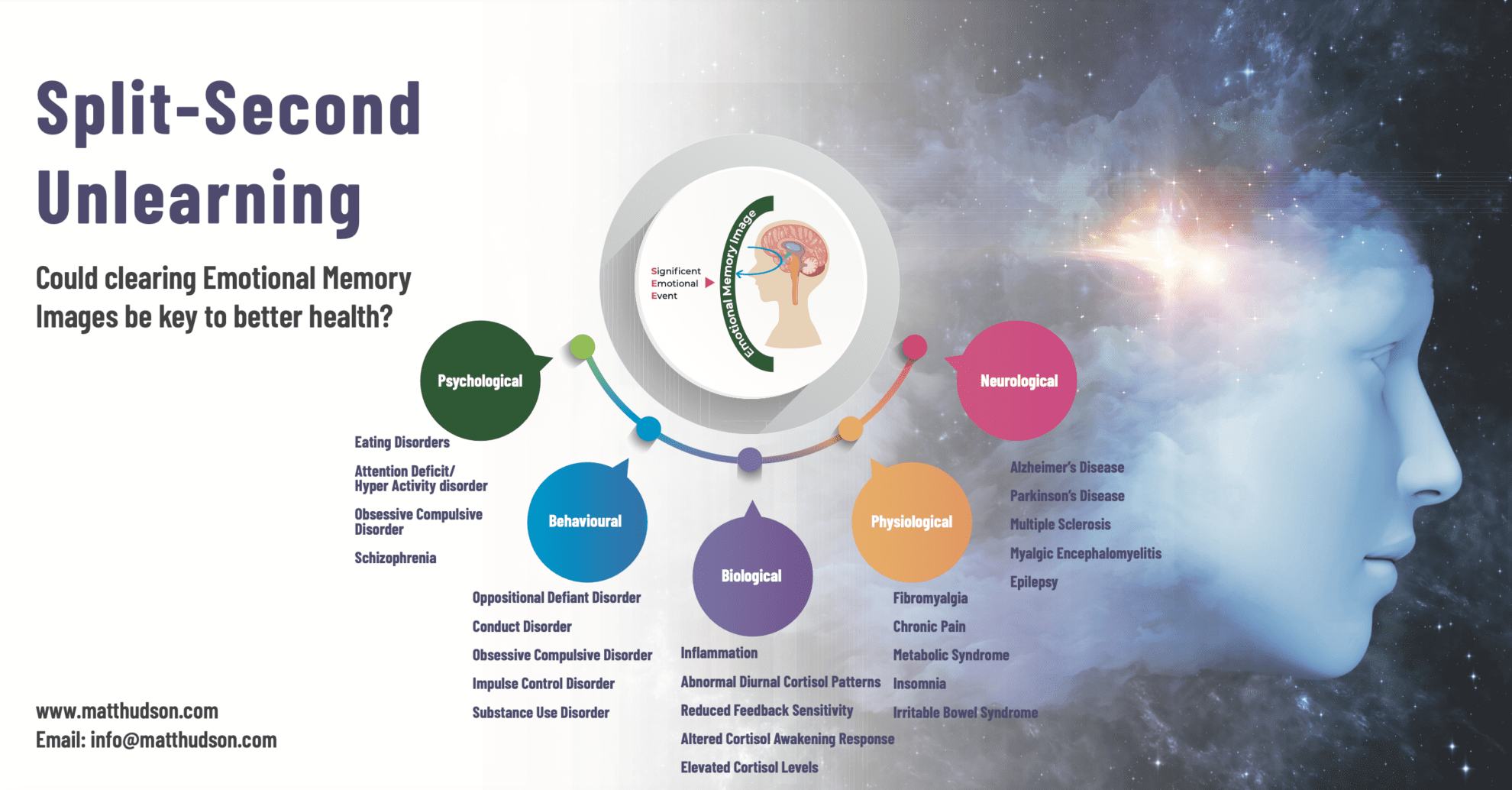

Integrating Forsdyke’s theory, the instantaneous activation of EMIs could reflect a form of non-local retrieval. The Split-Second Unlearning (SSU) model complements this by proposing that clearing an EMI requires disrupting its connection to this external storage system, rather than merely rewiring neural circuits. By severing this subconscious link, SSU may facilitate immediate relief from trauma’s emotional and physical residues, offering a paradigm shift in trauma therapy.

Binary Encoding of EMIs: Bridging Shannon’s Information Theory

Claude Shannon’s information theory, particularly his binary encoding framework of 0s and 1s, provides a compelling analogy for EMI dynamics. Within this model, an EMI might operate as a binary switch: ‘0’ denotes an inactive or cleared state (no triggered response), and ‘1’ indicates an active state (trigger engaged). This binary logic mirrors the subconscious mind’s rapid, often automatic decision-making.

When an EMI shifts to ‘1,’ it initiates a cascade of emotional and physiological reactions; clearing it resets the system to ‘0.’ The brain, functioning as a receiver, may process these signals from either local neural networks or extracorporeal sources, as Forsdyke suggests. In the SSU framework, the therapeutic intervention aims to flip this switch from ‘1’ to ‘0,’ disconnecting the trigger from its response. This aligns with Shannon’s emphasis on efficient, low-redundancy information transfer, highlighting the precision and speed of EMI alteration. (see this short video for more insight).

This synthesis also offers a novel perspective on conditions like sleep apnea, where unresolved subconscious triggers—potentially stored extracorporeally—may manifest as physical symptoms. Clearing these EMIs could thus alleviate both psychological and somatic effects, underscoring memory’s reach beyond traditional brain-body boundaries.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image src=”https://matthudson.com/wp-content/uploads/map-of-the-mind-300×225-1.jpg” _builder_version=”4.27.4″ _module_preset=”default” title_text=”map-of-the-mind-300×225″ hover_enabled=”0″ sticky_enabled=”0″][/et_pb_image][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.27.4″ _module_preset=”default” hover_enabled=”0″ sticky_enabled=”0″]

The Map Model: EMIs as Gateways to Liberation

The Map Model positions EMIs as pivotal barriers between subconscious constraints and personal liberation. As illustrated below, an EMI locks individuals into a freeze-stress response, anchoring them within fear-based beliefs and values that stifle growth.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_divider _builder_version=”4.27.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_divider][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.27.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.27.4″ _module_preset=”default” min_height=”332.8px” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.27.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_blurb title=”Unlocking the Potential of Emotional Memory Images” image=”https://matthudson.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/0-7c5fb33f-9793-4dc4-a3c6-17fdda71ee01-512×512.jpg” _builder_version=”4.27.4″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”]Exploring the transformative power of Emotional Memory Images reveals a pathway to personal liberation. By understanding EMIs as gateways to our subconscious, we can begin to dismantle the barriers that hold us back. This innovative approach encourages individuals to confront their fears and reshape their beliefs, fostering resilience and growth. As we delve deeper into the intricacies of memory, we uncover the potential for profound healing and self-discovery, paving the way for a brighter future.[/et_pb_blurb][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]