Introduction

Psychophysiological stress is a domain of study that explores how stress impacts the brain’s electrical activity, cardiovascular system functioning, and other physiological systems. It’s understood that stress is a response to internal or external challenges, aiming to enhance survival and fitness. This domain investigates the evolutionary, emotional, behavioural, and social aspects of stress and resilience[1]

The impacts of stress on both mental and physical health are vast and multifaceted. Chronic stress, in particular, is detrimental. Here are some of the ways stress affects health:

1. Mental Health:

- Mood: Stress significantly influences mood and overall sense of well-being

- Cognitive Functioning: It can impair cognitive functions leading to issues like reduced concentration and memory problems.

- Anxiety and Depression: Chronic stress increases the risk of anxiety and depression.

2. Physical Health:

- Cardiovascular System: Stress activates a physiological response that, over the long term, can contribute to cardiovascular issues like hypertension and heart disease.

- Immune System: It can suppress the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to infections.

- Musculoskeletal System: Stress can lead to muscle tension and other musculoskeletal problems.

- Other Systems: The gastrointestinal system, respiratory system, and others can also be adversely affected by stress.

Chronic stress triggers a long-term activation of the stress response system, leading to overexposure to stress hormones like cortisol, which in turn causes wear and tear on the body. The longer the stress persists, the worse its effect on both the mind and body. Individuals may experience fatigue, irritability, and a host of other symptoms. In the long term, chronic stress can lead to serious health problems, including cardiovascular disease and other psychophysiological disorders[2],[3]

Psychophysiological disorders, a category of conditions worsened or brought about by stress and emotional factors, exemplify the intertwined nature of psychological and physiological health. These disorders manifest real physical symptoms that are either produced or exacerbated by psychological factors, hence the term psychophysiological. The symptoms of psychophysiological disorders are real and can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life[4]

The relationship between stress and health is complex. Stress can affect health directly through autonomic and neuroendocrine responses and indirectly through changes in health behaviours. The science linking stress to negative health outcomes is well-established, underlining the necessity of effective stress management strategies for maintaining both mental and physical health[5].

Continuing from the impact of psychophysiological stress, it’s important to delve into the prevailing issues surrounding chronic conditions like anxiety, depression, phobias, and others. These conditions, often categorised under mental health disorders, have a significant interplay with stress, each influencing and being influenced by the other. Here’s a closer look at some of these conditions and the associated challenges:

1. Anxiety Disorders:

- Prevalence: Anxiety disorders are among the most common mental health conditions, impacting millions of individuals worldwide.

- Stress Interplay: Chronic stress is a known precipitant and exacerbator of anxiety disorders. Individuals with anxiety disorders often experience heightened stress responses to everyday situations.

- Treatment Challenges: Treatment often necessitates a combination of medication, therapy, and lifestyle modifications, with varying degrees of success and accessibility.

2. Depression:

- Prevalence: Depression, too, is a widespread issue, with significant societal and economic costs.

- Stress Interplay: Chronic stress can lead to or worsen depression. The physiological changes induced by stress, such as alterations in neurotransmitter levels and brain chemistry, contribute to depressive symptoms.

- Treatment Challenges: Finding the right treatment can be a lengthy process, and the stigma surrounding depression can impede individuals from seeking help.

3. Phobias:

- Prevalence: Phobias are common, with many individuals experiencing irrational fears that can limit their daily functioning.

- Stress Interplay: Phobic reactions are often triggered by specific stressors, and individuals with phobias may experience heightened stress responses.

- Treatment Challenges: Treatment typically involves exposure therapy, which can be challenging and emotionally taxing for individuals.

4. Other Chronic Conditions:

- Conditions such as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, and various psychophysiological disorders often have stress as a contributing factor.

- The chronic nature of these conditions can itself be a source of stress, creating a vicious cycle of worsening symptoms and increased stress.

Challenges and Concerns:

- Stigma: The stigma surrounding mental health conditions continues to be a barrier for individuals seeking help.

- Access to Care: Access to effective, affordable care is a significant issue, particularly in lower-income regions or communities.

- Holistic Approaches: There’s a growing acknowledgement of the need for holistic approaches to treatment that address both the psychological and physiological aspects of these conditions.

- Research and Understanding: Increased research is crucial to deepen the understanding of the interplay between stress and chronic mental health conditions, and to develop effective interventions.

The intertwining of psychophysiological stress with chronic mental and physical conditions underscores a complex health landscape. Addressing these issues necessitates a multi-faceted approach that includes reducing stigma, improving access to care, advancing research, and promoting holistic, individualised treatment plans. Moreover, public education on the impact of stress and the importance of mental health is crucial for fostering a more informed and supportive societal environment.

Split-Second Unlearning Theory

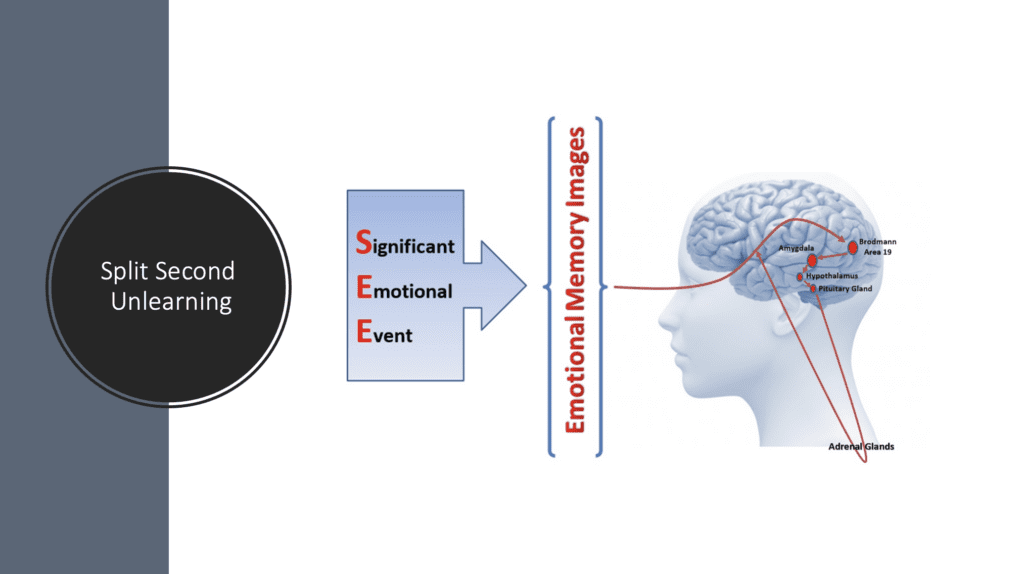

Hudson and Johnson’s Split-Second Unlearning Theory presents a novel lens through which to understand and address the intricacies of psychophysiological stress and its interplay with mental and physical health. This theory emphasises the formation of Emotional Memory Images (EMIs) as a crucial aspect of how individuals process and react to stressors. Unlike conventional viewpoints that may regard stress as a primary cause of mental and physical health issues, Hudson and Johnson pivot the narrative by positing stress as a symptom arising from EMIs.

The theory elucidates that significant emotional events, especially traumatic ones, in early life can induce psychophysiological “stress” responses, forming EMIs in very short timeframes, termed “split-second learning”[6]. These EMIs are mental images stored within the mind, formed from past emotional experiences, and are recognised as substantial barriers to a person’s ability to adapt to daily stressors and move forward. When triggered in daily life, these EMIs replay the psychophysiological stress responses, leading to a state of chronic psychophysiological “dis-ease”[7].

Hudson and Johnson argue that it’s these EMIs, and not stress per se, that are the root cause of various mental and physical health conditions. Stress, in this context, is seen as a manifestation of the underlying EMIs, essentially a symptom rather than a cause. The unlearning model they propose aims at addressing the core issue by helping individuals unlearn or detach these EMIs from the psychophysiological stress responses. By doing so, individuals can overcome the barriers posed by these EMIs, thus addressing the underlying cause of their stress and, by extension, the associated mental and physical health issues.

The therapeutic approach within the Split-Second Unlearning Theory involves scanning clients for mannerisms indicating a subconscious “freeze-like” stress response, engaging them as curious observers within their own experiences, and providing feedback on non-verbal cues as they manifest in real-time. This process helps clients dissect the observable fragments of their split-second Pavlovian response to the trigger, enabling them to detach their EMIs from the psychophysiological stress response, achieving what is termed as “split-second unlearning.” Through this unlearning, individuals can move beyond the barriers posed by EMIs, becoming naturally adaptive and improving their mental and physical health

This theory, therefore, provides a fresh perspective on the role of stress in mental and physical health, steering the focus towards addressing the underlying emotional memory images. The Split-Second Unlearning Theory by Hudson and Johnson presents a promising avenue for exploring more effective, client-centred therapeutic interventions that aim at the root causes of psychophysiological stress and its cascading impacts on health.

Understanding Psychophysiological Stress

Understanding psychophysiological stress entails delving into how psychological factors interact with physiological processes, especially under stressful circumstances. Here’s an in-depth explanation:

Concept of Psychophysiological Stress:

Psychophysiological stress involves the body’s physiological responses to psychological or emotional stressors. When faced with a stressor, the body responds by activating the stress response system, which includes the release of hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, increasing heart rate, and elevating blood pressure among other reactions. This response is often referred to as the “fight-or-flight” response and is aimed at preparing the body to react to the stressor.

Manifestation:

- Immediate Responses: Initially, stress triggers a rapid reaction in the body to prepare for the perceived threat. This includes increased heart rate, breathing rate, and a surge of energy provided by the release of glucose and fats in the body.

- Intermediate Responses: If the stress continues, the body may enter a state of resistance, where it tries to cope with the stressor. Physiological responses may normalise somewhat, but hormone levels, heart rate, and blood pressure may remain higher than usual.

- Long-term Responses: Chronic exposure to stressors can lead to long-term or chronic stress, where the body’s ability to return to a normal state (homeostasis) is impaired. This phase can lead to wear and tear on the body, known as “allostatic load.”

Long-term Effects:

- Mental Health: Chronic psychophysiological stress can lead to anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders. It may also impair cognitive functions like memory and concentration.

- Physical Health: It can also have detrimental effects on physical health, contributing to heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and other conditions. Chronic stress can also impact the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to infections.

Common Triggers and Relation to Emotional Memories:

- Triggers: Common triggers of psychophysiological stress include work-related stress, financial worries, relationship issues, and traumatic events. Even daily hassles can accumulate and trigger stress responses.

- Emotional Memories: Emotional memories, particularly traumatic or negative ones, play a significant role in how individuals perceive and respond to stressors. When faced with a stressor, emotional memories may be activated, potentially intensifying the stress response. Over time, these memories can form what Hudson and Johnson refer to as Emotional Memory Images (EMIs), which can be triggered by related stressors, leading to a chronic state of psychophysiological stress

Understanding psychophysiological stress and its intricacies provides a foundation for recognising its impact on individual and community health. It also sheds light on the importance of effective stress management and coping strategies, as well as the potential benefits of therapeutic interventions like the Split-Second Unlearning Theory by Hudson and Johnson. Through such interventions, individuals may find pathways to unlearning or detaching from harmful emotional memories, thereby mitigating the detrimental effects of psychophysiological stress.

Formation of Emotional Memory Images (EMIs):

Emotional Memory Images (EMIs) are central to Hudson and Johnson’s Split-Second Unlearning Theory. According to their theory, EMIs are formed within very short time frames during significant emotional events, especially traumatic ones, in a process termed as “split-second learning” When an individual experiences a strong emotional reaction to a particular event, this emotional response, along with the associated sensory information (like sights, sounds, and smells), gets encoded into a memory. This memory isn’t just a neutral recollection of facts, but a charged emotional memory image that can be triggered by related stimuli in the future.

Implications on Daily Living:

- Triggering of Stress Responses: EMIs can be triggered by situations, environments, or stimuli reminiscent of the original event. When triggered, these EMIs can evoke a strong psychophysiological stress response akin to re-experiencing the original emotional event, even if the current situation isn’t threatening.

- Influence on Perception and Behaviour: EMIs can affect how individuals perceive and respond to their environment. For example, a person with an EMI related to a traumatic car accident may experience intense anxiety or fear when driving or even when being in a car.

- Reinforcement of Negative Coping Mechanisms: Over time, individuals may develop coping mechanisms to avoid triggering these EMIs, which might include avoidance behaviours. While these coping strategies might provide short-term relief, they can reinforce the avoidance behaviour and limit personal growth and adaptation.

Implications on Overall Well-being:

- Mental Health: The continuous triggering of EMIs and the associated stress responses can contribute to mental health issues such as anxiety disorders, depression, or PTSD. The ongoing stress and anxiety can also impair cognitive functions like memory and concentration.

- Physical Health: The chronic activation of the stress response system due to EMI triggering can have detrimental effects on physical health. For instance, it can contribute to cardiovascular issues, immune system suppression, and other health conditions related to chronic stress.

- Quality of Life: EMIs can significantly affect an individual’s quality of life. The avoidance behaviours, chronic stress, and potential mental and physical health issues can limit personal and social functioning, reducing overall life satisfaction.

Development of Split-Second Unlearning Theory:

The Split-Second Unlearning Theory was developed by Matt Hudson and Mark I. Johnson as a means to address the chronic psychophysiological stress experienced by individuals. They drew from evidence suggesting that significant emotional events in early life, both traumatic and benign, could influence health and well-being later in life. They coined the term “split-second learning” to describe the rapid formation of Emotional Memory Images (EMIs) during these events, which become ingrained and are later triggered in daily living, replaying the psychophysiological stress responses.

Theory’s Premise:

The core premise of the Split-Second Unlearning Theory is the identification and addressing of EMIs as barriers to an individual’s natural adaptability to stressors. Hudson and Johnson argue that these EMIs are the root cause of chronic psychophysiological stress, rather than the commonly held notion that stress itself is the cause of various mental and physical health issues. They propose a model of “split-second unlearning” as a therapeutic approach to help individuals detach these EMIs from the psychophysiological stress responses. By doing so, individuals can overcome the barriers posed by these EMIs, becoming naturally adaptive once again and improving their mental and physical health.

The therapeutic approach involves scanning clients for mannerisms indicating a subconscious “freeze-like” stress response and engaging them as curious observers within their own experiences. Through real-time feedback on non-verbal cues, individuals can dissect the observable fragments of their split-second Pavlovian response to the trigger, facilitating the process of “split-second unlearning”.

Significance in Addressing Psychophysiological Stress:

- Root Cause Addressal: By targeting the root cause of chronic psychophysiological stress, the Split-Second Unlearning Theory provides a pathway for more effective and lasting solutions to mental and physical health issues arising from stress.

- Client-centred Approach: The theory emphasises a client-centred approach, placing individuals at the core of the therapeutic process. This empowerment can lead to more sustainable and self-driven progress in overcoming the challenges posed by EMIs.

- Holistic Understanding: The theory presents a holistic understanding of psychophysiological stress, bridging the psychological and physiological aspects of stress and providing a comprehensive framework to address the intertwined nature of mental and physical health.

Therapeutic Approach Proposed by Hudson and Johnson:

Hudson and Johnson propose a therapeutic approach within the framework of their Split-Second Unlearning Theory to address the Emotional Memory Images (EMIs) that underlie psychophysiological stress. The key steps of this therapeutic approach are as follows:

1. Identification of EMIs:

The first step involves identifying the EMIs that trigger stress responses in clients. This is done by scanning for particular mannerisms that signify a subconscious “freeze-like” stress response when certain topics or memories are broached.

2. Engagement as Curious Observers:

Clients are engaged as curious observers within their own experiences. They are encouraged to notice their reactions and behaviours in a non-judgmental manner, which can provide valuable insights into the nature and triggers of their EMIs.

3. Real-time Feedback:

Therapists provide real-time feedback on non-verbal cues as they manifest, helping clients to become more aware of their reactions and the associated EMIs.

4. Dissecting the Pavlovian Response:

By breaking down the observable fragments of their split-second Pavlovian response to the trigger, clients can begin to detach their EMIs from the psychophysiological stress response.

5. Split-Second Unlearning:

The process of “split-second unlearning” involves helping clients unlearn the automatic stress response triggered by EMIs, facilitating a more adaptive response to stressors.

6. Client-centred Approach:

This approach places the client at the centre of the therapeutic process, empowering them to take an active role in identifying, understanding, and addressing their EMIs.

Engaging Clients as Curious Observers:

Engaging clients as curious observers is a pivotal part of this therapeutic approach. Here’s how it can be beneficial in identifying and addressing EMIs:

1. Self-Awareness:

By adopting a curious observer stance, clients can develop greater self-awareness of their reactions, behaviours, and underlying EMIs. This self-awareness is crucial for identifying the triggers of psychophysiological stress.

2. Non-judgmental Exploration:

Encouraging a non-judgmental exploration of their own experiences allows clients to explore their EMIs in a safe and supportive environment. This can facilitate a deeper understanding of their emotional reactions and the associated stress responses.

3. Empowerment:

Being an active participant in the therapeutic process empowers clients to take control of their healing journey. It also fosters a sense of agency and self-efficacy, which are crucial for long-term success in managing and overcoming psychophysiological stress.

4. Enhanced Therapeutic Relationship:

The collaborative nature of this approach can also enhance the therapeutic relationship, creating a conducive environment for meaningful exploration and growth.

5. Promoting Adaptive Coping Strategies:

As clients become more aware of their EMIs and the associated stress responses, they can work with the therapist to develop more adaptive coping strategies. This collaborative effort can lead to more sustainable improvements in managing stress and improving overall well-being.

Case Study Examples

The provided case studies illustrate the application and effectiveness of Hudson and Johnson’s Split-Second Unlearning Theory in therapy. Through careful observation, the therapist identifies bodily cues indicating an Emotional Memory Image (EMI) trigger. Strategic interventions are then employed to dissociate clients from these EMIs, allowing them to objectively witness their stress response and engage in actively learning a new response. Both cases demonstrate successful outcomes, with clients experiencing significant relief from chronic conditions post-intervention, showcasing the potential of this approach in addressing psychophysiological stress and related issues.

Case Study One—Male, Aged 51

The client presented with trigeminal neuralgia (chronic pain), which he had been experiencing intermittently for 30 years. The medication made him nauseous. I (MH) asked him to tell me about his pain and the client noted, “It goes back to my bicycle accident,” which he went on to describe in detail. Over the course of about 20 min, I asked things like “What are you noticing, now?” This kept the client aware of the present whilst noticing their experience of the past. Part of the recollection was: “I had a vivid recollection of my father arriving to come and pick me up to take me home. He came into the room, took one look at me, went visibly white and had to leave the room to vomit, then returned.” At this point, the client’s eyes fixated on a particular spot out in front of him, his posture adjusted, he took a sharp intake of breath, the colour left his face, and his expression went blank. The total response lasted only a split second. I made a mental note of this action, which quickly faded as the client continued to recount his tale.

Intervention

When the client had finished his narrative, I directed him back to the point where he mentioned his father walking into the room. The client re-played all of the aforementioned body cues, suggesting that the experience of his father turning pale and vomiting was traumatic. I asked the client to pretend that he was watching the whole thing on a television over to his right. This would: (a) Have the client fixate his eyes in a different direction to the original EMI; (b) Dissociate the client from the EMI; (c) Allow the client to observe the EMI with me guiding the process; (d) Interrupt the SSU loop, allowing the client to integrate the EMI and move on from it.

The client welled up, he breathed deeply, and it was gone. The colour returned to his face, and he looked a little confused, which I interpreted as the brain reorganizing and updating information—the learned response was being “unlearned.” The stored EMI had left the client repeating the same neurological response over time, preventing any change in experience and perpetuating his pain. Clearing the EMI allowed him to disengage from the survival response, enabling new learning to take place and the split-second to roll forward in time. As the neurological connection with the traumatic memory fades, so do the physical effects of that memory.

The client has not experienced any pain since the intervention in April 2016. During follow-ups, their story has become more general and less detailed, suggesting that the EMI has been subsumed into their everyday background memory, which tends to fade over time and no longer causes the same physiological problem of chronic pain. In their words: “After the session, I lost the clarity of the pictures of my father coming into the hospital room. I do not seem to be able to retrieve that and much of the vivid detail of some of the experiences of the day of the accident is gone… I had seen my father’s face so clearly for so long but after the session, that memory was different—what remains is a very brief clip of him but no visual detail I can recall of any of the story.”

Case Study Two—Female, Mid-50s

During a 2-day training course, a lady asked if I would work with her. She shared, to an open audience, that she had been abused as a child by her father. She had completed various forms of therapy and by her own account did not feel traumatised; she had family and a good life. The only problem she had never been able to overcome, was her inability to have regular bowel movements. “Would it be possible for you to help me with this?” she said. As she asked this question, her eyes fixated on a point in her upper-right field of vision. At the same time, she raised her right hand as if to block her gaze.

Intervention

I asked her to hold that position and then suggested to her that despite all of her years of therapy there appears to be a piece of information that her body had not allowed her to see. I asked her to slowly lower her hand and give herself permission to access the information. At this point, she began to physically tremble, closed her eyes and reported that her brain felt like it was “sizzling with electrical connections.” After a couple of minutes, she opened her eyes, wiped away a tear and said, “Thank you.” She could not explain it but knew something had changed. The next morning, in an open round of sharing feedback from the previous day, she raised her hand and exclaimed, “I can poo for Canada!” Having been to the toilet before leaving her house, she was able to have a comfortable natural bowel movement without any effort, which was ground-breaking for her. Her bowel movements remained normal at 6 and 12-month follow-up sessions.

In these interventions, after identifying a set of subtle and fleeting bodily cues, the therapist relied on careful timing to deploy the interruption. Drawing on an applied phenomenological communication approach, commonly used in the caring professions[8]; [9], the therapist encouraged the client to focus on the present moment, while simultaneously prompting them to access and reflect upon their traumatic memory. This creates a discrepancy: on one hand enabling the objective witnessing of a memory and its associated reflex response; while on the other, interrupting/preventing the physical cues that cause a client to revisit that memory and subjectively re-experience it. Pragmatically, a well-chosen prompt, directing the subject’s conscious attention to the present, away from their EMI, allows them to become conscious of and objectively experience their stress response. Here, they can engage in actively learning a new (ideally neutral) response, rather than passively experiencing the usual traumatic reflex.

Implications and Future Directions

The Split-Second Unlearning Theory could potentially revolutionise therapy by addressing the root causes of psychophysiological stress. It may foster client-centred, effective interventions for chronic conditions. While specific ongoing or future research wasn’t found, the promising results from initial applications suggest that further exploration and refinement of this theory could significantly contribute to the broader field of psychology and therapy, enhancing our understanding of stress and trauma-related disorders. Encouragement of more research and clinical trials can help validate and expand this theory, potentially leading to more comprehensive and effective therapeutic approaches in the future.

Conclusion

The Split-Second Unlearning Theory by Hudson and Johnson offers a novel approach to addressing psychophysiological stress by targeting Emotional Memory Images (EMIs). Through client-centred interventions, individuals are helped to dissociate from these EMIs, fostering improved mental and physical health. While specific examples showcase the theory’s potential, further research and discussions within the therapeutic community are encouraged to validate and expand upon this innovative approach. Engaging with the Split-Second Unlearning Theory could open new horizons in therapy and mental health, and readers are urged to explore this theory further and partake in dialogues regarding its potential impact.

References

[1] Zakreski, E., & Pruessner, J. C. (2019). Psychophysiological models of stress. The Oxford Handbook of Stress and Mental Health, 486–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190681777.013.23

[2] https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/health

[3] Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., & Siegel, S. D. (2005). STRESS AND HEALTH: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 607. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141

[4] https://opentext.wsu.edu/psych105nusbaum/chapter/stress-and-illness/#:~:text=Physical%20disorders%20or%20diseases%20whose,psycho%20and%20physiological%20in%20psychophysiological

[5] https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

[6] Hudson M, Johnson MI. Split-Second Unlearning: Developing a Theory of Psychophysiological Dis-ease. Front Psychol. 2021 Nov 29;12:716535. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.716535. PMID: 34912263; PMCID: PMC8666476.

[7] Hudson M, Johnson MI. Definition and attributes of the emotional memory images underlying psychophysiological dis-ease. Front Psychol. 2022 Nov 14;13:947952. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.947952. PMID: 36452371; PMCID: PMC9702567.

[8] Bullington, J., Söderlund, M., Sparén, E. B., Kneck, Å, Omérov, P., and Cronqvist, A. (2019). Communication skills in nursing: a phenomenologically-based communication training approach. Nur. Educ. Pract. 39, 136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.08.011

[9] Zahavi, D., and Martiny, K. M. (2019). Phenomenology in nursing studies: new perspectives. Int. J. Nur. Stud. 93, 155–162.

Split Second Unlearning Theory